Overview of Site and History of Research

The present-day village of Kirrha, known as Xeropigado (literally “the dry well”) until the 1930s, takes its name from the ancient port of Delphi, alleged in these parts to be its distant predecessor. In fact, traces of habitation, a shrine, and the amenities of a port are in evidence from the end of the 6th century, as are Roman and Byzantine remains. Ruins of medieval fortifications are a reminder, too, that the port of Salone (Amphissa) was also located here. Today, the modern inhabited area is situated at the head of the Gulf of Itea and at the foot of the mountains forming the peninsula of Desphina, between the seafront and a small hill where the church and cemetery currently stand. This small hill is in fact the prehistoric tell that forms the principal object of this research programme.

The exploration of Kirrha and the Protohistory of Western Phocis

The Bronze Age is not entirely unknown in Phoci. Mycenaean levels have been explored in Delphi, while traces of occupation from the same period have been recognized in several other areas. These traces are sometimes quite significant, as they are on the neighbouring acropolis of Krisa. What distinguishes Kirrha from other prehistoric sites of the region is its lengthy inhabitation (the oldest traces date from the Early Helladic) and the fact that it has been known for a long time, with the first archaeological exploration on the site taking place in the 1930s. In those pioneering days of Aegean archaeology, the most important levels uncovered belonged to a period of proto-history (Middle Helladic and the beginning of Late Helladic) that was relatively unexplored at the time, hence Kirrha’s somewhat marginal position in Aegean studies: it was essentially pre-Mycenaean and situated in a region that was remote from the upheavals experienced in the great halls of Mycenean civilization. Under the influence of a revival in research, Kirrha’s marginal status has been on the wane for several years, as much from a chronological point of view as from a geographical one.

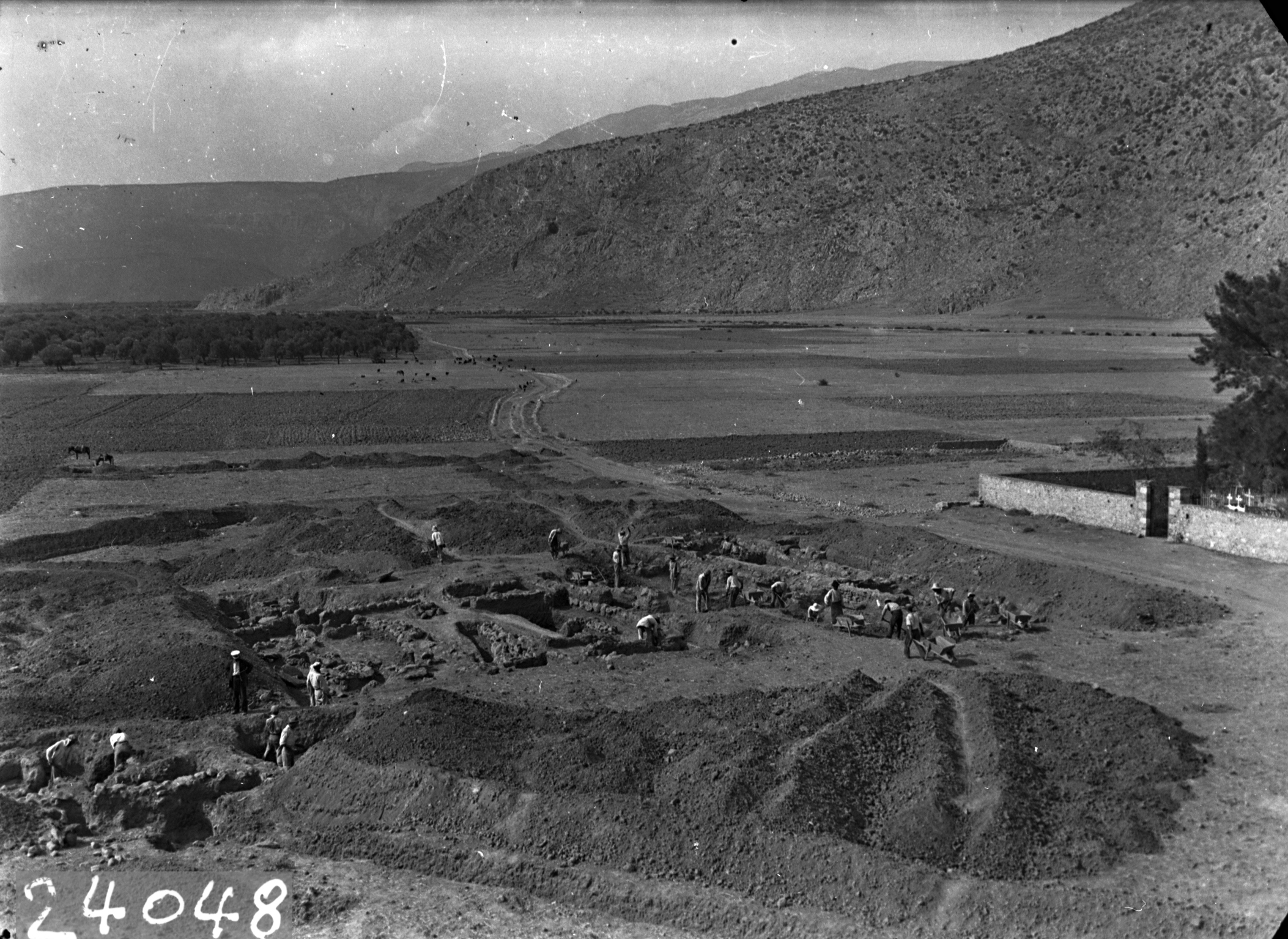

Excavation History: Pioneers in Rescue Archaeology

Kirrha’s tell was the object of a preliminary archaeological study between 1936 and 1938. Under the direction of J. Jannoray and d’H. van Effenterre, the tell’s summit was explored in two excavations campaigns of 1937 and 1938. Several relatively large sectors were opened and a stratigraphical sounding was taken, whose imprint is still visible today in the area’s topography, particularly to the north of the modern village. In addition to the village’s surrounding wall and the remains of the classical shrine, these different soundings allowed researchers to establish a timeline from the Early Helladic to the end of the Late Helladic. They also unearthed important remains of human habitation and tombs belonging mostly to the final phases of the Middle Helladic and the Mycenean era. The war brought an end to this research, the results of which would remain unpublished for some time. It was not until the 1970s that excavations began again on Kirra, in the form of a large number of urgent interventions led by the Greek Archaeological Service, necessitated by urban expansion. In the western part of the tell, these interventions unearthed sizeable craftwork facilities linked to the production of ceramics.

Research Programmes (2009 – )

The 2009-2015 programme

In 2009, the programme of excavations resumed in a collaboration (synergasia) between the Greek Ministry of Culture (Delphi constituency) and the French School at Athens. In its beginning stages, these new excavations had three principal objects of research: (i) the man/environment relationship; (ii) the archaeology of the habitat (based on studying the use of spaces and the exploitation of environmental resources); and (iii) the establishment of a system of chronology by examining closed contexts and absolute dating. But the discovery in the programme’s initial campaigns of a large number of burial sites had a dual impact: the human remains discovered represent a source of invaluable information for our own priority research areas, while the number and variety of the remains led us to consider establishing a programme specifically oriented towards funerary archaeology.

The 2017-2021 programme

The 2017-2021 programme of archaeological research at Kirrha is directly continuous with the preceding one, whose research objectives it aims to complete. With respect to funerary archaeology, for example, the programme should bring to completion the excavation of the West necropolis (see “Excavations: campaigns 2009-2015”), while an ambitious programme of laboratory analysis is also planned that will use molecular DNA determination, radiocarbon dating, and analyses of stable isotopes to analyze the entire funerary population of Kirrha. Inspection of the superficial layers containing the tombs of the transitional period (HM III – HR I/II) will allow full access to the underlying Mesohelladic habitat, the study of which was a research priority in the initial programme. Finally, important discoveries were made concerning Kirrha’s origins, both in relation to the archaeology of landscapes (following the results of environment research conducted between 2009 and 2015) and with respect to the artefacts found (with the discovery of a sizeable neolithic beacon on a large section of the tell). These discoveries require efforts to be continued in this direction, notably through the use of deep cores on the summit of the tell and through intensive exploration of its entire area.

Preliminary Results

The tell and its environment

Environmental research questions are at the heart of this programme and were envisaged prior to the first campaign of excavations. It was not so much a question of understanding how the small hill was formed (which stands today at a height of 8-9 metres above sea level) since we know that it is the result of an accumulation of debris. What was at issue was the rationale behind the choice of the site itself. The questions posed concerned two kinds of issues: (i) the relationship between the prehistoric village and the two water currents running through the plain today; and (ii) the relationship between the habitation site and the sea. These questions are now close to being answered, thanks to initial results from a programme of geomorphological study of the plain and the latest data on variations in sea level in the Gulf of Corinth. It already appears that the current coastal situation was markedly different in ancient times, and that the tell of Kirrha, contrary to the picture it presents today, was in fact a peninsula surrounded by water.

Excavations: 2009-2015 Campaigns

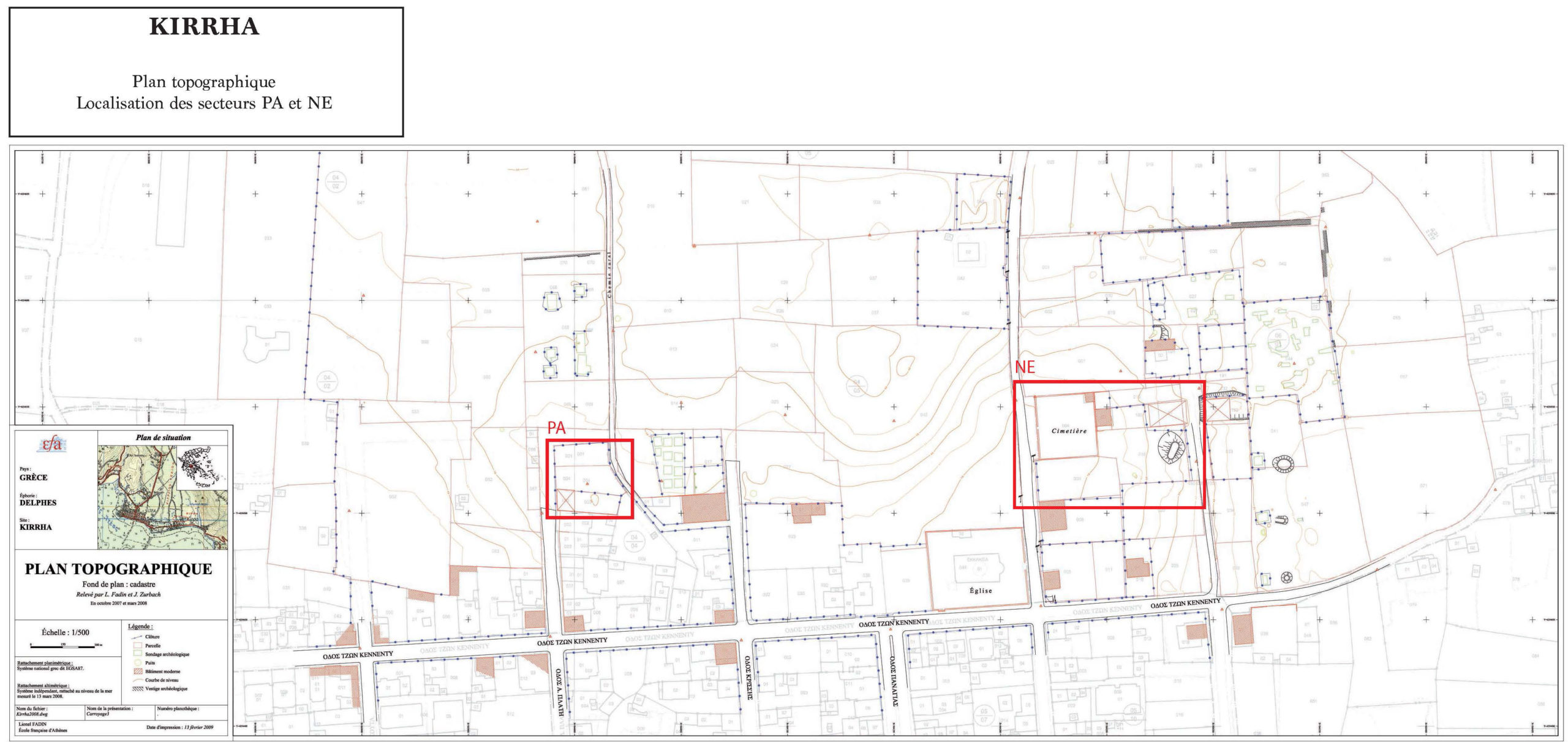

The tell’s summit, the site of the village church and cemetery, represents the current urbanisation frontier of the modern urban area. This means that research on the site must take into account existing buildings and zoning. Two plots were given to us: a communal site to the east of the cemetery and, at the other end, an expropriated plot of land on the western edge of the hill.

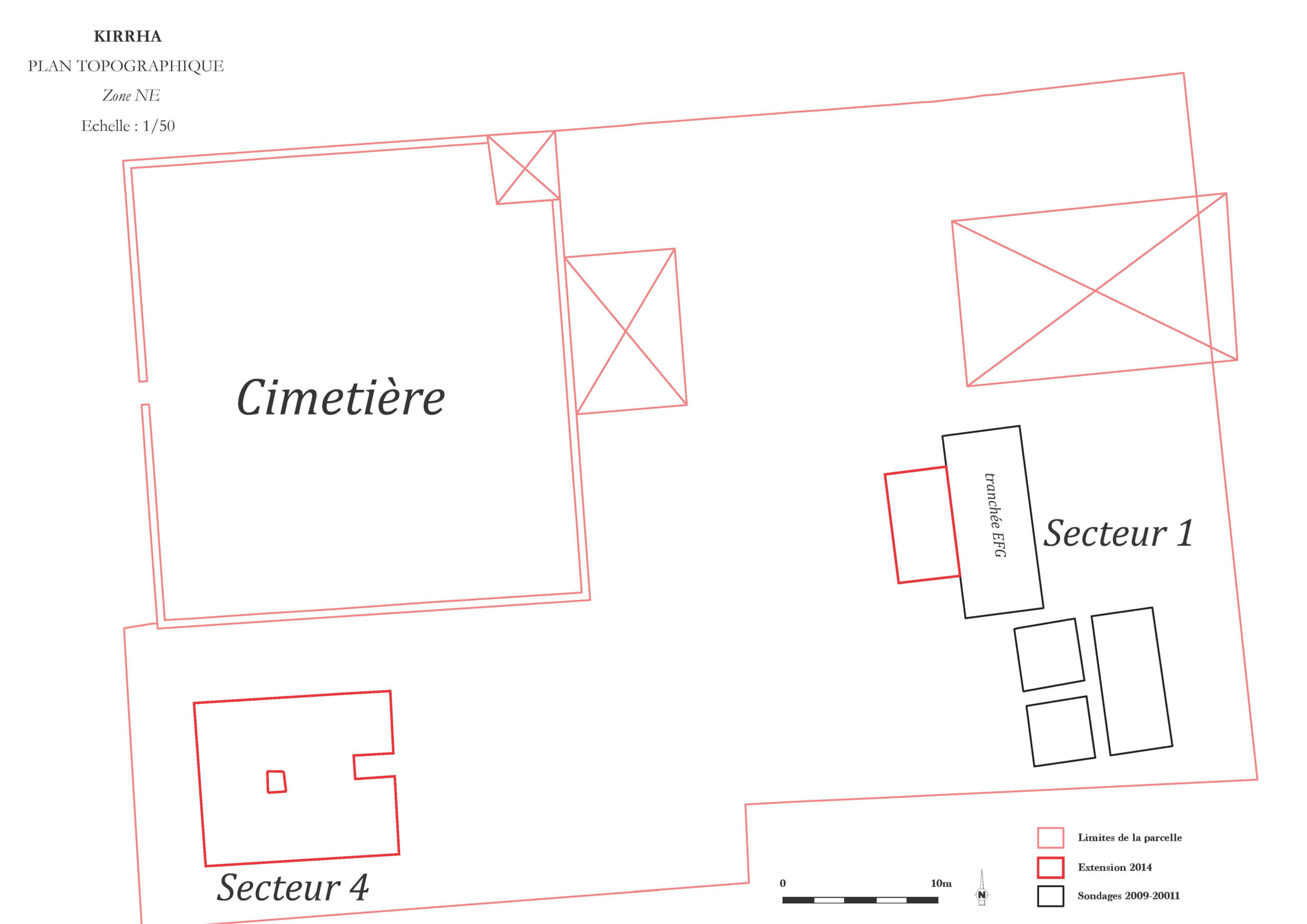

The NE zone (east)

The campaigns lead in 2009, 2011, 2014, and 2015 allowed the opening of about 220m² of the tell in this zone, close to important architectural and craftwork remains that had already been unearthed by Archaeological Service excavations in preceding decades. The discoveries made were of various kinds: to the south of Sector 1 (squares A, B, C, and D), the 2009 and 2011 campaigns unearthed strips of gravel soil at different levels, suggesting the presence of exterior facilities, probably connected to the craft activities indicated by the presence of two small potter’s ovens at the beginning of the Late Helladic. Also found in the same zone were a circular hollow containing, for the most part, a large quantity of vases from the Mycenaean era and bowls (HR III A1 and A2). The large EFG trench dug to the north of Sector 1 and explored from 2011 onwards brought to light substantial architectural traces, including notably the exterior wall of an east-west building and an intersecting wall, giving the outline of two rooms, so far at least. In addition to floors prepared using earth and to material that would have been common in a home (wedge stones and stone surfaces), the East space revealed the remains of a pithos clearly crushed on site, whose large size and remarkable production quality make it a particularly exceptional piece. It was found accompanied by a small jug with painted decoration, attributable to HM III and thus providing the date of the edifice’s abandonment. To the north, where the levels contemporary to the latter site were disturbed by later additions (wall segments and bottom slabs), and in the south where preparations for exterior floors referred to above are being discovered, a number of burials of very young children indicate that the following phase saw the conversion of the zone into a children’s funerary space. To the west of the NE zone, close to the modern cemetery and church, a large trench was dug in 2014, which constitutes Sector 4. Several architectural phases dated by ceramics from HR IIIB confirm the presence on the tell’s summit of a habitation, probably of modest size, during the palatial period. These are clearly traces of habitations which, beyond the remains of buildings whose form and dimensions are difficult to reconstruct for the moment, have revealed a characteristic domestic set up (communal ceramics, in place storage vases, stone tools, etc.). In 2015, the discovery of a child’s burial site in Sector 4—although we cannot yet say if it is primary or secondary—confirms the importance of a tradition previously established in Kirrha and elsewhere and which continued there during the Mycenean period, with the permanent provision of children’s burial sites in the inhabited area.

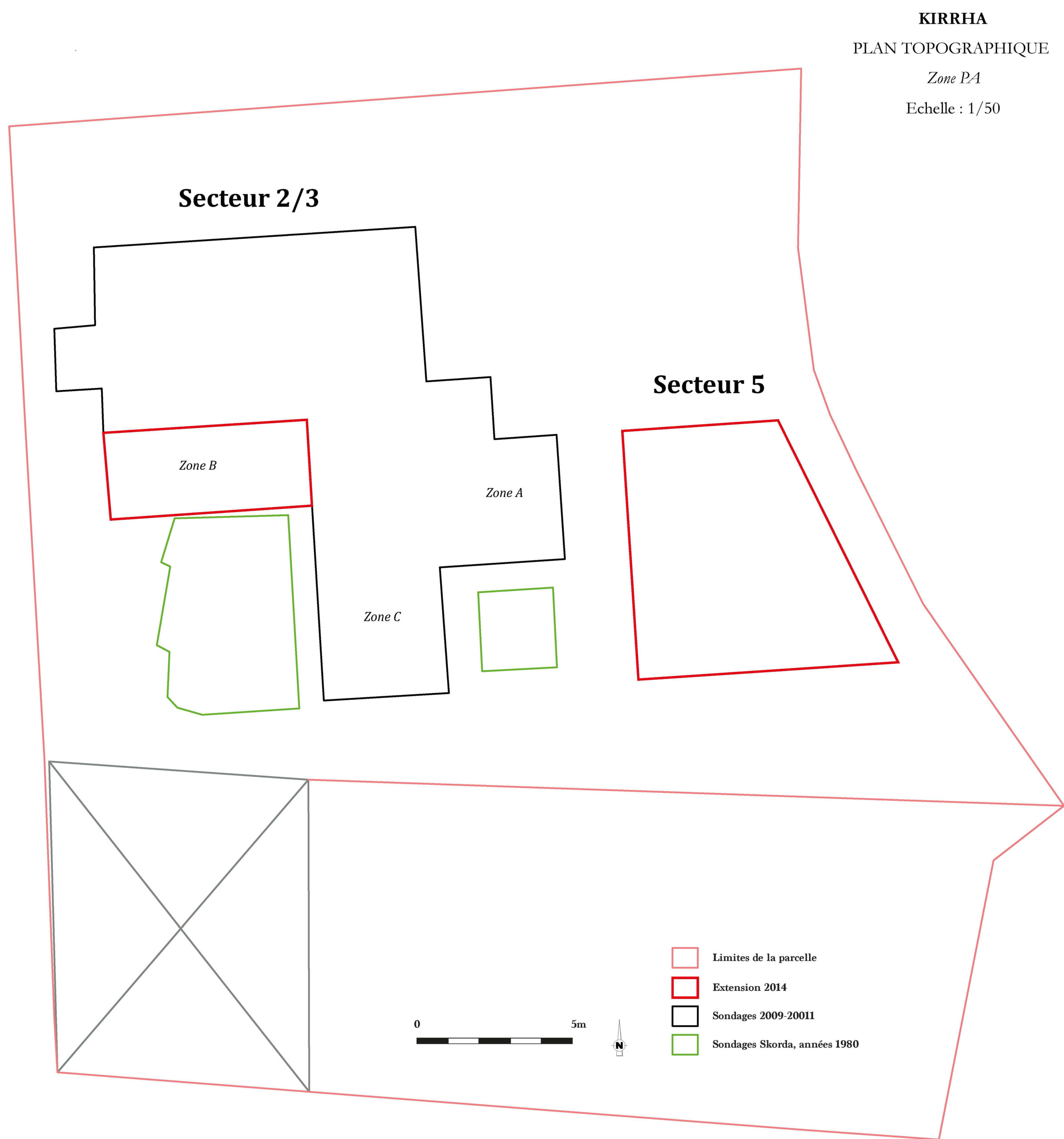

The PA zone (west)

The plot explored to the west of the tell had previously been the object of excavations led by the Archaeological Service. At a depth of about 1m below the modern surface, these excavations revealed a succession of Middle Helladic constructions. These indicate the presence of a dense and lasting habitation. Three rectangular soundings have been taken since 2009, subsequently brought together and extended to form a single area of about 150 m² (Sector 2/3), accompanied since 2014 by Sector 5 to the far west of the zone (55 m²). The campaigns of successive excavations shed light on the upper levels and facilitated the general organization of the zone. The final occupation phase (phase A: end of HM / beginning of HR) is characterized by the presence of an important number of burial places—about thirty at present—and an even higher number of individuals as a minimum, the zone presenting a very great variety of burial forms and funerary practices, unequalled to this day for that particular period. This necropolis had been established on the ruins of the final phase of the sector’s habitation (phase B), represented in segments of walls whose state of conservation makes them difficult to analyze. The following phase (phase C) involves a level of occupation established on the ruins of the underlying habitat and represented by several elements: wells, low walls, etc. The oldest phase we have reached (phase D) is represented by architectural traces in a better state of conservation, in the form of two buildings whose extent is still unknown. The first, in the north-west, had a floor of beaten earth where a hearth had been put in place, while in immediate proximity to the second building, in the south-east, a child had been buried in an amphora placed in a well. This burial, contemporary to phase D, should allow us to date the latter in quite precise terms. Moreover, systematic analysis of human remains will clarify the chronological outline and rhythms according to which the necropolis was used, at a period for which absolute dating still remains a relative rarity.

Bibliographical Orientation

The Excavations of the 1930s

Dor H., Jannoray J., Van Effenterre H., Van Effenterre M., Kirrha, étude de préhistoire phocidienne, Paris, E. de Boccard (1960)

Excavations by the Archaeological Service

D. Skorda, « Η σωστική ανασκαφική δραστηριότητα στον προϊστορικό οικισμό της Κίρρας κατά το 2000 », in Αρχαιολογικό έργο Θεσσαλίας και Στερεάς Ελλάδας : πρακτικά επιστημονικής συνάντησης Βόλος 27.2 – 2.3.2003, Εργαστήριο Αρχαιολογίας Πανεπιστημίου Θεσσαλίας, Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού (2006), Βόλος, p. 657‑675.

D. Skorda, « Κίρρα: οι κεραμεικοί κλίβανοι του προϊστορικού οικισμού στη μετάβαση από τη μεσοελλαδική στην υστεροελλαδική εποχή », dans A. Philippa-Touchais, G. Touchais, S. Voutsaki, J. Wright, MESOHELLADIKA – MΕΣΟΕΛΛΑΔΙΚΑ. La Grèce continentale au Bronze Moyen – Η ηπειρωτική Ελλάδα στη Μέση Εποχή του Χαλκού – The Greek Mainland in the Middle Bronze Age, École française d’Athènes (2010), p. 651-668.

The Programme in Progress

Annual reports have appeared in the following volumes of the Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique : 133.2 (2009), p. 565 ; 134.2 (2010), p. 545-549 ; 135.2 (2011), p. 535-539 ; 136-137.2 (2012-2013), p. 569-592 ; 138.2 (2014), p. 691-693.

R. Orgeolet, D. Skorda, J. Zurbach & alii., « Kirrha 2008-2015 : un bilan d’étape, 1. La fouille et les structures archéologiques », BCH 141.2 (2017), forthcoming.

A. Lagia, I. Moutafi, R. Orgeolet, D. Skorda, J. Zurbach, « Revisiting the Tomb: Mortuary Practices in Habitation Areas in the Transition to the Late Bronze Age at Kirrha, Phocis », in M.J. Boyd & A. Dakouri-Hild, Staging Death: Funerary Performance, Architecture and Landscape in the Aegean, DeGruyter (2016) p. 181-205.

© EFA / R. Orgeolet, 2016.