Major phases in urban development

Delos, a place of pilgrimage

At least until the third century, it seems that the urban area was not much developed. Chosen by Leto during her wanderings as a place where she could give birth to Apollo and Artemis, at the foot of a palm tree that from then on was sacred, Delos soon was and always remained a famous cult site. Accordingly, it became a place of pilgrimage, festivals and contests, where its neighbours sent sacred ambassadors. It was around the sanctuary or rather sanctuaries of the small northeastern plain, bordered by a cove where ships came to moor, that the town spread radially outwards, in a way that it is not easy to determine precisely, since we have a good knowledge only of the most thriving era of the second to first centuries BC, under the second Athenian domination.

-

- Speculative restoration of the town of Delos at the end of the second century BC

-

-

Overall view of the northeastern plain

Delos in the Independent period:

The urban expansion of the Independent period is still not very well known. Nevertheless, a cult regulation dated to 202 BC suggests that in this period the areas to the north and east of Apollo’s sanctuary were not yet occupied by any buildings:

‘… let the area near (the altar of) Dionysus remain clean and let no one throw, either in the clean area or the temenos of Leto, any dirt, nor ashes, nothing…’. (Bruneau, Recherches sur les cultes de Délos…, p.305)

Some other pieces of information obtained from the numerous inscriptions on stone found at Delos make it possible to deduce that the town of the third century, and even the first half of the second, was not densely populated (with a population of possibly 6000), and extended over an area much smaller than the one we see at the beginning of the first century when, due to a lack of space, it unashamedly even spread over sacred land. The inscriptions from the Independent period refer to rented houses by the sea, or near the port, and to another near the theatre.

It is clear that the ungoverned, if not confused, growth of the Theatre Quarter, with its housing that varied greatly in size and layout, gives the impression that the district to the south of Apollo’s sanctuary must be older than the one that developed to the north. The term 'insula', traditionally applied to a group of houses, is scarcely adequate here; it would make more sense to speak of unforced urbanisation. The houses joined each other in every sense, with a twisting main road of a very variable width, that of the Theatre, onto which looked many shops, alleys, which sometimes broadened into crossroads, and cul-de-sacs. The hotchpotch of interlocking houses, with their party walls, is in contrast with the individual style that each of them seems to have shown.

-

-

The Theatre Quarter

The theatre itself (114), built in the second third of the third century for around 5000 spectators, with an noteworthy cistern (115), ended up no longer on the edge of the town but rather surrounded on all sides by housing, a large hotel (113), and some small sanctuaries. Further east, what is known as the Inopos Quarter, after the name of the island’s only watercourse, seems to have also been inhabited as early as the Independent period, according to both epigraphic and archaeological data.

-

-

The Theatre Cistern (115)

-

- The Theatre (114) and Hotel (113)

Delos as an Athenian colony

As it grew, the Athenian town encroached upon sacred land and gardens (known from inscriptions, to the north and east of Apollo’s sanctuary) which were then displaced to the outskirts. The island’s narrowness and its hilly landscape did not leave much of a choice. So the town was also obliged to climb towards the slopes of Cynthus, and in general it sought to use the variations in the level of the ground as best it could: this resulted in roads that were stepped or sharply sloping, and a certain penchant for semi-basements and indeed tiered housing, on the seafront and in the House of Hermes (89), which leans on a slope to the south of the sanctuary of Apollo, not far from a temple of Aphrodite (88) dedicated towards the end of the fourth century. The town was not afraid to make gains from the sea by means of embankments, as is attested by the dedication of a statue erected in 126-125 in what is known as the Agora of Theophrastos, to the northeast of the sanctuary, near a large hypostyle hall (50) that must have been a meeting place and perhaps a trading centre.

Still to the north of the sanctuary of Apollo, housing was extended in a way that displayed a kind of concern for regularity; in this case, although it is not possible to speak of an urbanisation programme as distinct as at Olynthus, Priene and elsewhere, nor of a true Hippodamian plan with a regular grid, there are insulae of different sizes and roads that are a little less narrow than on the theatre side and orientated north-south/east-west. They have retained a significant network of covered drains. Nevertheless, the urban fabric is still dense.

Amongst the major dwellings there is the Establishment of the Poseidoniasts from Berytos (the ancient name for Beirut) (57), a place to stay and meet for Berytian traders. It is one of the symbols for the extraordinary cosmopolitanism of this town, which brought together, alongside Syrians, Phoenicians, Egyptians and even Jews, all in a greater or lesser state of Hellenisation even though they brought their respective cults. As well as the Athenians, one of the most prominent foreign communities was that of the Italians, who seem to have lived in the island’s northern districts in particular, including the Stadium Quarter (78). These districts were in fact distinctive for having many altars near the entrances of houses, and for the presence of colonnaded streets, as at Herculaneum, where these columns supported an overhanging storey, balcony or loggia, constituting a private annexation of public land. In time, owing to the lack of available flat ground, the large and indispensable collective establishments for educational purposes, of the gymnasium(76)/palaestra/stadium/hippodrome(75)-type, were also extended to the north.

-

- The gymnasium (76)

-

- The Stadium Quarter

The squares

Between the sanctuary of Apollo and the Sacred Lake, on a piece of sacred ground that had previously been empty, the powerful Italian traders built their huge meeting space, which had multiple uses, towards the end of the second century (the Agora of the Italians, 52). This private establishment had the form, and ultimately the name, of an Ionian agora, nicely framed by porticoes on two levels.

It was a counterpart to the Agora of the Delians (84), built from the Independent period onwards to the south of the sanctuary of Apollo, on the same type of plan: this paved rectangular square, which was used for political purposes before being devoted to trade, was surrounded by colonnades divided by passageways and which opened onto warehouses and shops. The Agora of the Delians, which was endowed with exedras, fine rectangular or semicircular marble seats with wide backs that were crowned with statues, which adorned the whole civic and religious centre, was separated from the port area by a path (the Dromos, 2-5) bordered by the imposing Stoa of Philip (3).

-

-

The Agora of the Delians (84), the Dromos (2-5), the Stoa of Philip (3)

-

- The Agora of the Italians (52)

This was well placed at the end of a fourth agora, close to triangular in shape, which represented the most important connecting crossroads in a town that otherwise lacked small public squares. Indeed, this agora, of the Competialists or the Hermaists (2), named after the rich dedications from the associations of Italians that had established their places of worship there, was passed through by all who disembarked and embarked again at the port, whether they were pilgrims heading for the sanctuary of Apollo or merchants coming and going in the Theatre Quarter and in the northern districts, which ran the length of the quays.

-

- The Agora of the Competialists or the Hermaists (2)

The port

It is not known exactly to when this ‘sacred’ port dates, and it is in any case possible that in the Archaic period another landing stage, further to the north, played a vital role, before the corridor of movement was inverted in favour of the area to the southwest of the sanctuary. All the same, it was in the period when it was declared a free port (167-166 BC) that it experienced its greatest expansion, as Delos then lived for and by it. The quays were paved, a line of warehouses was built to the south, and several docks have been identified in what is now termed an emporion.

Further north, in the direction of the bay of Skardhana, which had the role of a secondary port, dwelling houses were also mingled with utility buildings. In a sense, the port area displayed the characteristics of the Delian urban area in microcosm. Although the sacred never lost its entitlements, with its altars and chapels, housing and commercial establishments were constantly intermingled.

After the brutal invasions of the first century BC, changes in trade routes led to the decline of Delos as a port of call, as it could no longer attract traders and other shipowners. The French excavations have given back to the sacred port some of its standing, by building the large south breakwater, where today caïques put in, out of their rubble.

The houses on Delos

Private residences of the second and first centuries form the great majority of buildings on Delos and, by comparison with other sites in Greece, constitute one of the chief unique characteristics of Delos from an archaeological point of view.

All the houses are grouped into districts, of which only three have so far been partially excavated, those of Skardhana and the lake (59-66), the stadium (79), and the theatre (117). It seems that these districts were not specialised, either according to the wealth of their inhabitants (as the most splendid homes are found next to the simplest) or their ethnic background: in spite of the cosmopolitanism of the population, all Delian houses are of the same type. When – exceptionally – it is possible to determine the occupants’ nationalities, it seems that the houses of people from the same place were distributed in different districts: so at the beginning of the first century a house in the Stadium Quarter (79), the House of Hermes (89) and, probably, that thought to be of Philostratus of Ascalon (99) were also Italian homes.

-

- The House of Hermes (89)

The chief characteristics of private architecture

The layout of the houses on Delos was of a type usual in ancient Greece: the centre of the home was formed by an courtyard around which the different rooms were ranged. The house turned its back on the road on which it stood, at least on the ground floor, with blind walls punctured only by one or several doors. This was the general construction principle, although it could be applied in countless different ways.

Only in the wealthiest homes did the central courtyard have a peristyle, and even then the type of peristyle and number of columns varied considerably. The columns were very often of the Doric order, but generally only the upper part was fluted in the canonical style; in the lower part, only the edges were cut. Two houses, those of the Masks (112) and the Trident (118), have a sumptuous variant termed by Vitruvius a ‘Rhodian’ peristyle.

-

-

The ‘Rhodian’ peristyle of the House of the Masks (112)

The rooms are arranged in a variety of different ways and are sometimes not found on one of the sides of a house due to a lack of space. It is often very difficult to be specific about how they were used. Some, with their ample dimensions and rich decor, can be identified as reception rooms (one was generally larger than the rest; it is known as the oecus maior as opposed to smaller boudoirs and living rooms, the oeci minores). On the sides that bordered the road, houses sometimes had a row of separate rooms that opened onto the outside. These were premises used for trading or artisanal purposes. These shops are found especially along main roads like the Street of the Theatre (120) and ‘Street 5’ (121.1) and along the port (122; see also the warehouses of the Granite Monument, 54).

Generally the houses had one storey, and sometimes several. The restoration of the insula of the House of the Comedians (59 B), in general one of the most original groups on Delos, will give an idea of what a Delian house of the Hellenistic period was like.

-

- The insula of the House of the Comedians. Restored model.

-

-

The insula of the House of the Comedians (59 B)

To build these houses, a range of materials were used, often together, which were generally sourced from the island’s quarries: marble, granite and poros (which, being lighter, was used for upper storeys especially) have been found. It was gneiss, however, that was by far the most commonly used and which gave Delian walls their very distinctive look. This rock, like schist, is easy to break off, especially at Delos where, after separation, the layers of gneiss were split with vertical joints; in this way rubble stone of all shapes and sizes was produced. The unevenness of the unit was disguised by a thick stucco wall coating. The floors of rooms were often covered with mosaics, generally of one colour but sometimes decorated.

In the absence of public fountains, water was supplied by cisterns and wells – some of which were also fed by rainwater and helped to maintain the water table.

House decoration

What seems to distinguish housing on Delos from that of other sites is a broad taste for decoration, which often gives a house its name. It shows the inhabitants’ high standard of living, which can already be discerned in the oil lamps that were unsparingly used, and the crockery made of varnished pottery (with or without embossed designs) and also glass.

-

-

Mosaic showing Dionysus on a cheetah. Found in the House of the Masks (112).

Mosaics have been discovered in remarkable numbers at Delos, both on ground floors and upper storeys. They can be simple mosaics of shards (amphora fragments) in utility rooms, or of small or large fragments of marble on terraces or in a courtyard with a cistern. Frequently, however, especially in reception rooms, luxury products are found, either in the form of a central panel made using more advanced techniques that resembles a carpet with geometric motifs, or a full piece like the one found in the oecus (reception room) of the House of the Tritons (59 B) and which was removed in ancient times already, while we have its neighbour, which depicts a Tritoness and an Eros in fourth-century style, following an archaising trend. Although the pieces in opus vermiculatum, like the famous Dionysus riding a tiger, are exceptions, the trompe-l'oeil ‘carpets’ in opus tessellatum present interesting variations, even as far as doormats.

-

- Mosaic showing a Tritoness. Found in the House of the Tritons (59 B)

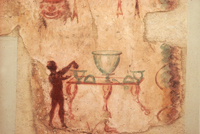

The paintings that survive at Delos, despite not being fully professional works and being in a somewhat fragmentary state, constitute an unusually valuable source of information, which gives an idea of what ‘pictorial civilisation’ was in Greece proper, in one of the Hellenistic world's most evocative centres. All these paintings date from the second and first centuries. They take the form of friezes that adorn the walls of the main rooms in the most elaborately decorated private houses, and so are an integral part of wall decoration as a whole.

-

-

Wall painting showing a small servant.

-

-

Banner showing a chariot race. Found in the Granite Palaestra (66)

-

-

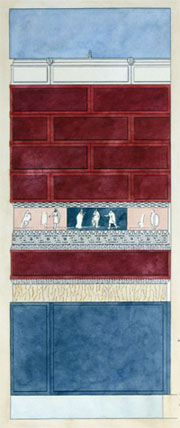

Restoration of a painted wall (House of the Comedians, 59 B)

In order to protect the masonry and give it a uniform look, the house walls were generally covered with a coating that in most cases was decorated in a more or less elaborate fashion. Taking into account variants in its execution that could alter considerably the way it looked, the method of decoration on Delos was always imitation of large-scale, regular masonry work: simply making incisions in fresh mortar could trace the outlines of the ‘blocks’. However, the use of colour, in lines or blocks, and of relief-work, gave the structure greater definition. Decoration was divided into four zones, which matched the successive heights of the scaffolding necessary to carry out the work as a whole. Each of these zones, separate in decorative terms, could in turn be sub-divided into several horizontal units. Research into decoration focuses on the middle zone, at eye level.

This ‘structural’ system of decoration was paralleled elsewhere in the Hellenistic world from the end of the fourth century onwards: it has been found in Macedonia, Athens, Cnidus, Samothrace, Thera, Alexandria, Palestine, Magnesia on the Maeander, Pergamon, Priene, and southern Russia, but also Rome, Sicily, Spain, and Italy. Today it seems that the oldest forms of decoration at Pompeii and Herculaneum, traditionally known as the ‘First Pompeian Style’, were a regional variation of this international style which may be termed the ‘large-scale masonry style’ and of which the Delian houses almost certainly offer the richest and most representative examples.

In addition to this so-called (due to its dependence on architecture) Greek structural style, attention should also be drawn to the discovery in the House of the Sword of a painting that is so far unique to Delos, and of a concept that is radically different as it is related to the ‘Second Pompeian Style’, which seeks to depict a whole architectural space in perspective. With shades of pink, red and green dominating, a garland of vegetation in the form of a festoon hangs from the capital of a trompe-l'oeil Corinthian colonnade.